Eric got up at 6 a.m., afflicted almost immediately with thoughts of Misty's disappearance. He put up coffee, trudged to the bathroom, back to the kitchen. In the dim glow of a small amber nightlight, he fixed a bowl of kibbles for Buddy, the new dog.

Carrying a cup of coffee, he stepped outside. The predawn sky was charcoal dark, cloudy and cold. Snow fell silently, covering rocks, trees and the front yard with a smooth white blanket. Rounded curves, flowing lines, sensuous textures. Clean. Pristine. But Eric hardly noticed the beauty.

Somebody stole her, he thought. Couldn't have been otherwise. She was too big to be attacked by coyotes, and certainly not in the front yard. I checked the fence lines, nothing. Searched the meadows and forest nearby. Animal shelters didn't have her. Ads in the paper. Followed every lead. Neighbors said they heard her barking and howling that day two months ago. Somebody yanked the lock-chain off the fence, tied it to her collar, packed her into a car or truck, hauled her off. Probably because she was so beautiful, intelligent, friendly. They liked her. Might have been as simple as that.

On the other hand, maybe not. . . Damn. . .

Eric finished his coffee, went back inside, put on his cowboy hat and wool-lined jean jacket. "Come, Buddy." The dog looked at him, unsure, cautious. "Come on," Eric whispered, opening the front door.

They walked together down to the meadow by the stream. Snowflakes fell softly in the muted light, like feathers settling gently to earth.

He discovered a heap of black-and-orange woodpecker feathers under a maple tree. Earth and moldy leaves had been churned up and scattered in the night. Pain and death here. Then quietude, balance restored, harmony. The natural cycle.

Eric inserted one of the feathers into his hatband; gathered others, stashed them in his jacket pocket.

Buddy trotted ahead in the meadow, sniffing bushes, lifting his leg and spritzing, rambling on, sticking his nose into the same rabbit holes Misty used to explore. Eric's breath rose in mist-clouds. The snow fell faster and heavier, feeling good on his face.

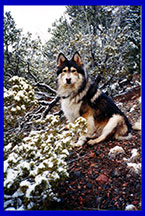

A month ago, Simone visited the animal shelter. She spent time with several dogs, but when she saw Buddy, she knew immediately he was the one she wanted. He lay alone on a cement floor in a dark wire cage at the back of the building, where hardly anybody ever looked. He was a medium-sized dog, two or three years old, 60 pounds, black and tan fur, pointed ears, brown eyes, broad paws, a long tail, a handsome cross between a wolf, collie, malamute and mutt.

Lying alone on the hard cement floor, chin on his paws, he looked frightened, depressed, hopeless. When Simone walked him on a leash outside, his body trembled. A skittery dog, hyper-sensitive. Apparently abused by some ego-tripping sadist, Buddy had escaped and run away. He survived by raiding trash dumps and campground garbage cans, begging for handouts, stealing food, hunting rabbits. He then got caught in a "humane trap" and brought to the pound. End of the line. Simone's heart reached out to him. She brought him home.

Buddy loved and responded to Simone, but it was doubtful if he had ever experienced love or kindness from a man. As a result, he shunned Eric. Even simple, non-threatening gestures, the wave of a hand in conversation, a sudden turn walking through the kitchen, sent Buddy scuttling away, tail between his legs.

Buddy's behavior intensified Eric's misery. Misty had been stolen. Now this dog feared him. He had hoped a new dog would ease his sorrows. Instead, he felt worse.

Nevertheless, he and Simone remained patient and kind. They spoke to Buddy in loving tones. No violent gestures. Reprimands in only the gentlest ways, expressing disapproval, not through volume and rage, but quietly and firmly, sometimes in whispers.

After two or three weeks, Buddy began to understand and trust Eric a little more, perceiving him less as a generalized male threat, more as an individual. Eric and Simone felt pleased he was blossoming well, his confidence growing steadily.

Back home after the walk in the meadow, he propped the woodpecker feathers in a cup on his desk. Poured another coffee. Tried to answer a letter from his old friend Steve, couldn't.

They had to have stolen her. Why hadn't the neighbors checked on the barking and howling? And why had he insisted Misty stay home alone? Too sunny that day, too hot inside the truck. Damn, damn, damn. . .

At 8 a.m., Eric scraped ice off Simone's car windshield and checked the oil. Simone's loveable 1980 red Datsun, Ruby, had been last-leggin' it for three years. Ruby almost always needed oil, especially in winter. He poured in a quart, closed the hood, warmed up the engine.

Simone and Eric had cried at Misty's loss. Now neither of them spoke of it. They accepted the slow, burning pain in their stomachs, tried not to dwell on it. Better not to talk. Be gentle with each other, sensitive to nuances. Let time pass.

He gave Simone a kiss and waved good-bye as she left for work. Ruby disappeared down the hill, the sound of her motor fading away in grey morning light.

Eric stood with Buddy in the yard, listening to the quietude, his heart aching. It couldn't have been a bobcat or a bear, either. Broad daylight. Front yard. Misty weighed 70 pounds. Other animals too small to hurt her. She loved us, would never have run away.

A gust of wind blew hard. Snow fell again, rounded and gritty like tiny hailstones, click-ticking on Eric's hat and on the shoulders of his faded jean jacket.

When Simone left for work these days, the house turned lonesome, cold and still, almost lifeless.

He sighed. Breath-clouds vanished in wind. Snow fell steadily. He didn't want to go back inside. Impossible to write. He decided to take another walk, not down to the meadow again, but over the red-earth hills on the other side of the road.

He reached into his pocket for the key. Buddy seemed to know they were going for a walk. He wagged his tail hesitantly, still apprehensive, but less so than a month ago.

Locking the front door, Eric wondered how in God's name anybody could treat him badly. Isn't it enough that people degrade and slaughter each other? Apparently some people aren't satisfied with that. They have to beat up loving creatures like Buddy, too, before they feel good inside.

I know there are exceptions, he thought, pulling his collar up against the chill. God bless the gentle ones. They lead us toward the light. Long may they live. They know a well-treated dog is kind, courageous and devoted. He knows how to love. More importantly, he knows how to awaken love and compassion in the human heart. How can anybody not see that?

Eric checked his boot-laces. We can learn so much from animals, he thought. I never saw a beaver fell more aspen than he needed for his house. There is no such thing as greed in the wild. The woodpecker feathers I found are a sign, not of violent chaos, but of balanced harmony. In the midst of nature's giving and taking, benevolent serenity shines its golden light on all alike. No animal kills for sport or malice, only for food, territory, defense. Animals have survived millions of years. If we only listened to them, they could teach humanity how to live peacefully throughout the world.

I once thought that might happen, Eric said to himself, adjusting his hat. Now, I'm not so sure. You can move from L.A. to an isolated adobe house on the side of a hill in New Mexico, and they'll still steal your dog.

He pulled on his gloves, stepped off the porch into the snow, shut the front gate behind him, walked across the dirt road. A blue-and-white real estate sign had fallen down on the other side. Eric stepped over it. Buddy pissed on it. They hiked up the hill together, Buddy moving ahead like a scout.

When Eric and Simone moved to New Mexico three years ago, they often took walks, either in the meadow down by the stream, or over the hills on the other side of the road.

"I love those hills," Simone said one day. "Sometimes I'd like to walk there by myself, to my lookout place. I could sit and look across the valley, or close my eyes and meditate and just be peaceful inside. But I have no sense of direction. I'd get lost, I know I would."

"Come on," Eric said. "We'll mark a trail for you."

He and Simone walked together, tying short strands of bright blue knitting yarn to cedar and pine branches every ten or twenty feet on both sides of the trail. At Simone's favorite promontory, they looked over the arroyo and across the valley to the Jemez mountains 20 miles away. Moving on, they marked the trail another mile or so, until it met the dirt road that led back up to the house.

When they finished, they smiled and hugged each other, and named it the Blue Yarn Trail. Simone didn't follow it very often, but when she took occasional walks by herself, she was grateful for the security it gave her. The Blue Yarn Trail was her friend in the wild. It seemed to carry her loving, gentle presence even when she was not there.

Today, of course, in deep winter, the blue bows hung from their branches encrusted with ice and snow. Eric could hardly see them, but that was okay. He knew the trail. And he liked the weather — low clouds, gently streaming snowflakes, the atmosphere cold, close, quiet.

Following Simone's trail, Eric and Buddy came to a large, circular clearing where, over a hundred years ago, Nambe and Tesuque Indians used to camp while hunters sought game in the nearby higher mountains.

Today, Eric didn't see any pottery shards. He didn't hear ancient spirits. Nobody chanted around a bonfire. No medicine men imparted courage to warriors. No wizened shamans taught the young ones respect for the earth. Nobody cooked or danced or sang or prayed to the gods.

Cold winds whispered heartache through the pines.

Eric and Buddy walked around the ancient circle's perimeter to a place where the ground seemed to drop off into nowhere, the slope descending 300 feet to the arroyo below. At the edge, they turned left on the ridge and followed the Blue Yarn Trail to Simone's lookout.

Eric peered through snow flurries across the arroyo to the other side. . . Snowstreams slanting in wind. . .Cedar trees dusted white. . .Wet earth, deep red, shading into burgundy, faintly luminescent.

For a few moments, he stood still as a statue, gloved hands in jacket pockets, breathing without sound.

Whichever way the weather, Eric thought — rain, sun, snow — Simone loves the view up here. She wants me to leave her ashes under that bush if she dies first. Well, I might sprinkle a few, but then again, I might keep her intact, so to speak. Carry her with me in a jar. Vanish into Mexico, maybe San Miguel de Allende. Drink myself to death, not rapidly or dramatically. Quietly, slowly, no big deal. String it out. Prices are good there.

He called Buddy with a whisper. Buddy came to him and sniffed his gloves, then licked his wrist, a new gesture. Eric smiled and patted his head. Following the trail, they continued walking, sometimes along the edges of steep, quick drops.

Snow covered the top sides of cedar and juniper boughs. The undersides remained dry and brown. Wet red rocks, richly darkened by mist and snow, seemed to glow like lava coals.

His cowboy hat grew heavy with snow. Without brushing the brim off, he kept walking, noticing little, crunching snow underfoot, his mind drifting in and out of dreams. Occasionally, he woke up and watched Buddy running down hills, among trees and bushes, loving the cold and snow, the scents of coyotes, rabbits, an occasional deer, once in a while a bear that had crossed the trail in the night.

Often Buddy came back to Eric, as if to say, "You still with me?" When he sniffed Eric's hand, Eric snapped out of his self-absorption for seconds at a time. Clearly, Buddy trusted him more. He petted his dog, smiled, talked to him gently. When Buddy left, Eric's eyes glazed over. Thoughts streamed on. Part of him wanted to connect with Buddy and the trail; another part droned underground, helplessly remembering, imagining. . .

A man who had seen Eric's ad in the paper called and said, "Hispanics and Indians steal dogs, you know, use them for dog fights and gambling. They always need new dogs for the pit bulls."

. . .Misty surrounded by men with drunken, bloodshot eyes, pulling her on a rope, waving money, shouting, cheering, laughing, drinking, yanking her into a blood-drenched arena, hitting her, yelling at her to enrage her and make her fight. She, wild-eyed, struggling to get away, pit bulls snarling across the arena, fangs bared, attempting to get loose and rip her apart. Misty totally disoriented, mortally terrified, chaos, pain, fear — Where am I? Where are my people? Why am I here? What awful things are they doing to me?

Horror in the heart.

Eric stood still, his backside to the wind, covered almost entirely with snow, staring blank-eyed into space, unmoving, like a tree. Several minutes passed. Buddy whined uncomfortably, pawed the earth, looked up at him anxiously. Eric turned toward him, wondering who he was, why they were there, his eyes staring through Buddy as if he didn't exist.

Buddy dropped to his front paws, his tummy touching the ground, his rear end up as if stretching. He barked, trying to connect. The sharp sound startled Eric.

"Yes," he smiled, returning from far away. He beckoned to Buddy. The dog approached, relieved, wagging his tail. He leaned his head against Eric's thigh, comforting him, even as he asked for comfort himself. "Good boy," Eric whispered, petting him.

It takes a while to come back, he thought. . .What a good boy. . .What a kind, gentle friend.

Just a few days ago on the phone, a different voice said, "I got your dog."

The man described a silver-grey, 70-pound shepherd mix, pointed ears, brown eyes, a happy disposition. Sounded like Misty.

"When can we get together and work this out?" the guy asked.

"I can't this morning," Eric said. "I have a dentist appointment, but. . ."

The guy hung up.

Eric hated himself. He should have said, "Let's get together immediately. I'll give you a reward, no questions asked." But he didn't.

He felt convinced that this guy was the thief; that he did have Misty; that the low-life bastard had sold her to dog fighters by now. I blew it, he thought. The one chance I had, and I blew it.

He felt guilty for not responding to Steve's recent letter. Haven't been very good company since Misty vanished, he thought. Even if I wrote, I'd only depress him.

He kept walking, eyes turned inward. Trees passed unseen; cold winds blew unheard.

No writing today, he muttered. Just hike and go home. Play guitar and watch taped football games with the sound off. Step outside, chop wood. Maybe not. Maybe write Steve anyway. Hell, I don't know.

Accept the situation, he thought, sitting under a pine tree overlooking the hills. Don't dwell on the loss. Don't keep repeating images. Stop obsessing.

He listened to snow pellets clicking on tree branches above him, some falling on his hat and shoulders. Ice formed in his beard as he sat with his back against the tree trunk, hands in jacket pockets. He tried to feel the frozen earth beneath him, but his mind wandered. . .

A man on the phone said, "You the guy lost a dog?"

"Yes."

"Well, we saw a black and white Elkhound-husky get hit by a truck on Aqua Fria two days ago."

"Two days ago?"

"Yeah — sorry, but didn't see your ad 'til today."

"You have the dog?"

"No. The truck ran over it, broke its right rear leg. Tore it almost half off. Couldn't see if it was a male or female. Wouldn't let us get close. She ran across an empty field, howling, dragging her leg. It was hanging by the skin."

In his mind's eye, Eric saw Misty from an aerial view, looking down upon her as she struggled across the field, heaving her mangled leg behind her, white bones stabbing bloody snow, hearing her cries, seeing her confusion, feeling her pain and unfathomable loneliness, her unbearable need.

Eric's heart was breaking.

That very day, he drove to the place. No Misty. No other dog. No bloody trail. Wind whistled through a barbed wire fence, whirled snow across a barren field of sorrows.

Will suffering never end?

Quite unexpectedly, Buddy flopped down in a snow-patch in front of Eric, ears perked, a smile on his face. He barked, snapping Eric out of the dream, then barked a second time, louder.

At first, Eric didn't know what he wanted. Buddy jumped up, then flopped down again, his front paws on the snow, rear end high, tail wagging like a flag. Buddy wanted to play!

He nuzzled his muzzle into the white powder, pushing ahead like a dolphin swimming in snow-waves. Sitting under the tree, Eric smiled, then laughed aloud. Buddy leaped to his feet, ran to Eric and jumped on his chest, almost knocking him over. He ran away a few yards and stopped, looking back, laughter in his eyes. Seeing what Buddy wanted, Eric stood up, gave a "Whoop!" and waved his arms in the air.

They trotted down the slope side by side, leaping a few feet across a narrow ravine, landing together on the other side like a team. They hustled up the far slope, Buddy in the lead.

Fun. It was fun. Eric had almost forgotten fun. He smiled at Buddy and clapped his gloves together, huffing a bit from the exertion. My God, how long it's been. . .

For a few moments the gloom-cloud had lifted. Brooding had stopped, his mind had cleared, a new energy warmed his body. Buddy made it up the other side. Wagging his tail, he turned and watched Eric climb, enjoying the fact that here was a human who liked to do these things, too.

From a cleft between two steep inclines at the top of the hill, a small trickle of melting ice-water wended its way down the other side toward the fanned out arroyo below. On both sides of the rivulet, falling snow covered trees, logs, rocks, bushes, cacti. Wet earth and moist rocks glowed deep red. Left behind from autumn, leaves dangled from wet-black scrub oaks like russet-orange decorations.

Eric stood quietly under a pine tree, breathing slowly, hands tucked in his jacket, thinking about the quality of his life and about his old friend Steve. Falling snow blanketed his hat, shoulders, the sides of his arms, the tops of his boots. He stood still as stone, staring into space. Gritty snowflakes tapped pine boughs near his ears. Trickling water tinkled quietly in chill air. Far away, almost inaudibly, distant freeway traffic whisper-hummed.

Buddy came to him, tail wagging, sniffed his hands, licked his wrist. Eric smiled warmly, pleased with these new displays of affection. Buddy was awakening, coming back to life.

How can I write to Steve? How can I be cheerful or witty? Am I able to turn my attention toward something other than my own misery?

Probably not. No.

Plus, Misty's loss is not the only pain I would inflict upon him. That fundamental ache triggers off other hurts as well, dredging up a thousand doubts and self-criticisms. Pain bubbles up continually. . .

Misty's loss affects everything I think and feel. Is my vision simply colored by her loss? Maybe nothing's colored at all. Maybe I just see the unadorned truth clearly now. My life is utterly stupid, a pathetic series of dismal failures — in writing, in music, earning a living, communicating with others. Work, friendship, creativity — zot. Maybe that's the truth. Maybe Misty's loss has given me the real picture. Maybe I ought to feel grateful she's gone.

Thank God Simone is here. She keeps me busy and responsible, and we love each other. I play guitar at the hotel twice a week. That feels good. As for the rest of it, well, not a lot to brag about.

Sure, I've visited "the depths." And I've been "to the top of the mountain." So what? When you return with good news about how people can change their lives for the better, does anybody care? I don't think so. They say they want to change, but they don't. They like their misery. It gives them identity and pleasure, puffs up their egos. Climbing the mountain may be good. But telling others what you found? Stupid. Plus, who the hell am I to tell anybody anything? Maybe

I'm the one who likes the misery, not them.

Buddy whined and wagged his tail, impatient to get on with the hike. "Of course, Buddy," Eric whispered. "How thoughtless of me. Where are we? Ah, yes, the Blue Yarn Trail."

Look at these markers, he thought. They light the path like little blue stars. God bless Simone. Her presence brings love and warmth and hope even when she's away. Maybe life is not so bad. Maybe it's just easier to remember heartbreak than it is to remember love.

And look at this dog, he thought, petting Buddy's head, scratching behind his ears. Warmhearted, sensitive, gentle. Such a kind and loving soul.

"And look at your bright smile!" Eric said aloud.

Happy with Eric's tone, Buddy romped a few yards down the trail, turned and looked back, brown eyes cheerful, tongue out, tail wagging.

Eric nodded and smiled, pointing his finger away from the trail, over the rim, down the steep incline to the arroyo below. "Come on, big fella, let's see what you got."

Buddy cocked his head, "Down that?!"

Eric clapped his hands and leaped over the edge. "Let's go!" Buddy reared up on his hind legs like a horse and instantly dashed after Eric.

Eric ran fast, in giant steps, crunching snow and wet gravel beneath his boots. His body felt strong, his legs sure. With quick turns, reversing directions, he whipped around juniper trees, bent low beneath cedar branches, darted around cactus stands, hopped over rocks, spun sideways in mid-air over eroded gullies.

Initially, Buddy ran beside him, delighted, then surged in front, running faster than Eric, focused intently, agile as a wolf. They tacked from side to side down the steep incline, zig-zagging around trees and boulders, leaping over logs and ravines like deer.

Eric's mind felt clean and clear, fully present, no yesterdays or tomorrows, no regrets or anxieties. If his attention strayed for even a split second, he would crash into a cactus. If he didn't set thinking aside and attune his body with the land, responding immediately to the curves, dips, bumps and crevices hurling past him, he'd find himself impaled on a cedar branch or wrapped around the trunk of a juniper tree.

Effortlessly, his mind remained empty and calm, as serene as a lake, as spacious as sky. Stones, bushes, cacti and trees streaked past him in a blur. His body felt light and quick, twisting and jumping and sliding without hesitation, merged in movement with the slope's contours like flowing water or rushing wind. He felt present within his own body, fully alive in-the-now, thrilled with the danger, the pleasure, the exhilaration of this singing, bright-light moment.

In a certain way, his sensations felt new and somewhat strange. No thinking. No time. No pain. Only here and only now existed for him in this mad-dash rush down the hill, and he wasn't used to that. In another way, this careening moment felt absolutely natural and true. Suspended in space, transcendent. Outside of time, eternal. Serene tranquility in the midst of extraordinary activity. From emptiness in action, the birth of wondrous being.

At the bottom of the hill, he stood in trickling snow-water, hands on knees, gasping for air, eyes flashing, face radiant. Blood pumped in his veins. He could hear it in his ears. It had been months since he felt this good. Buddy stood panting a few feet away, eyes dancing, tongue out, tail wagging. He rushed up and gave Eric a big slurpy kiss across his cheek and nose.

"Ha!" Eric laughed, hugging his dog, nuzzling his face in his fur. "Aren't you the superjock! What great fun, eh?"

Reconnecting with the Blue Yarn Trail, they followed it along trickling waters to a juncture where the water disappeared in sand and the arroyo fanned out wide, heading toward the road that led back home.

Look at this place, Eric said to himself. Stop for a minute, and just

look where you are.

Large, soft snowflakes floated down from grey-white clouds that hung so low Eric could almost touch them. Red-earth canyon walls rose high in luminous mist on either side, topped with ghostly cedar and juniper trees. Waves of snowcapped chamisa lined both sides of the arroyo. Snowdunes languished from bank to bank. Rabbit tracks, bobcat prints, coyote tracks and deer tracks criss-crossed in snow, disappearing among bushes. Stones and boulders glowed; trees subtly pulsated. Eric breathed deeply. Air filled him with light.

Fifty yards away, Buddy stood astride a boulder, framed by cacti and chamisa, looking at Eric through space, time, and veils of snowflakes.

A month ago, he had been a beaten, trembling creature, abandoned in a cage, doomed unless saved by an angel. That's when Simone had found him.

Today, here he was, standing tall on that rock, regal, like a wolf-husky prince, vital and robust, in full health, confident and strong. His true nature had flowered. What a handsome dog.

Eric and Buddy stood still, looking at each other. Streamers of falling snow enclosed and united them within a single glistening moment. . .

Eric raised his chin slightly. "Come," he whispered. Buddy cocked his head quizzically to one side, eyes sparkling, ears pointed. Eric leaned forward, clapped his gloved hands softly, whispered again, more clearly, a smile in his voice, "Come."

Buddy jumped off the rock and bounded toward him. He leaped into his arms, tumbling Eric backwards, licking his nose, cheeks, eyes. They fell into a drift together, frolicking in snow, Eric laughing aloud. Buddy leaped up and away, still playing, dashing toward the dirt road a hundred yards further on.

He stopped, turned back. "Come on, Eric," he said with laughing eyes. "Isn't this a great day? Let's go!"

Chuckling, Eric stood up, brushed the snow off and adjusted his hat. He followed Buddy up the road toward home, smiling all the way, dazzled by the beauty of the earth and sky around him.

Rio En Medio, NM

January19-21, 1993